The Udmurt Language

The Udmurt language belongs to the group of the Finno-Ugric languages. Although the Udmurts have been living in close interrelationship with Turkishlanguage (Tartar, Baskir, Chuvash) and Slavonic-language (Russian) speaking people for centuries, they preserved their linguistic (and cultural) independence until recent times. However, due to the social and political changes in the last century practically the entire Udmurt-language speaking community has become (at least) bilingual (trilingual with Tartar in the Southern areas). In the generation of the present grandparents there still can be found, albeit very rarely, monolingual (Udmurt) speaking people. Consequently, present-day speakers are indigenous, bi- or trilingual people living in minority position.

On the basis of empirical observations it seems that in the second part of the last century the nature of primary linguistic socialisation: the acquisition of both the Russian and Udmurt languages happens in early childhood, often simultaneously.

The formation of the Udmurt literary language, the setting of linguistic norms started in the 18th century. The standard usage of the language, however, is still not regulated in detail, since in consequence of the established social-political circumstances the Udmurt language is not used at all or used only in a limited way on several domains of language usage in spite of the language revival endeavours which took off in the last decade. Among others the education in the mother-tongue is also insufficient. Therefore present-day speakers use their mother-tongue either only at the level of dialect or at the level of both dialect and standard language.

The knowledge of Russian and Udmurt languages shows recognisable differences among the generations.

People over 60 considered their knowledge of Udmurt very good but of Russian not that satisfactory. Only a couple of them declared a mastery of the Russian spoken language. The middle-aged speak nearly as good Russian as Udmurt, and they read and write better in Russian. The youngest generation

understand, speak, write and read significantly better in Russian than in Udmurt.

The speakers generally find the difference between the dialect spoken by them and the standard language significant. The oldest generation know the Udmurt standard language only very little, they can speak only the dialect. The differences between the dialect and the standard language listening comprehension and speaking fluency decrease among the younger generation but still prevail, so the knowledge of Udmurt in dialect is at a higher level for all the generations than the knowledge of the literary Udmurt.

The two main places of language acquisition for all speakers are their home and school, but there are recognisable divergences of language acquisition among the generations. At home the elderly speakers learnt only Udmurt, and so got to know Russian at school or later in their adult lives. Presently the simultaneous or successive (i.e. in succession) but always childhood language acquisition is typical of the method of language acquisition. The present-day youth and young middle-aged have been or are taught Russian as well or only Russian already by their parents in order to avoid being at a disadvantage at school. Language competence differs according to age: as in general the elderly are dominantly Udmurt speakers; the younger generations are balanced bilingual or dominantly Russian bilingual.

The type of language acquisition is dependent upon the status of the languages involved: Udmurt has a lower acceptance in the society, familiarity with it does not help individual mobility, it does not offer useful knowledge in the areas of economy and trade. The speakers do not believe that their skills increase with the knowledge of more than one language or with studying in their mother-tongue. All of these logically create a favourable situation for subtractive bilingualism.

The role of the school in the Udmurt language acquisition is significant for each generation, it comes directly after the home: as the school is the place of learning literary Udmurt.

A great part of the present-day youth cannot hand the Udmurt language down to their children because of their own insufficient language competences. Therefore in the future the teaching of Udmurt and the education in the Udmurt language should be a much greater role given. Moreover, grandparents still speaking a very fluent Udmurt could take on a significant part in language acquisition. However, under present-day circumstances both possibilities are mere illusions which cannot be realised without effective external support, institutional help and a definite raise in the prestige of the language.

On the basis of the differences in number between the speakers of the two contact languages and because of other circumstances that are not linguistic it cannot be expected that the use of the minority language dominates outside family circles. However, by now Russian also became a family language beside (or instead of) Udmurt with the generation of the middle-aged and the urban population of the Udmurts playing a key role in it. On the whole, it is still the use of Udmurt that dominates in the family, but on the scenes of community life it is pushed into the background in the cases of all the generations.

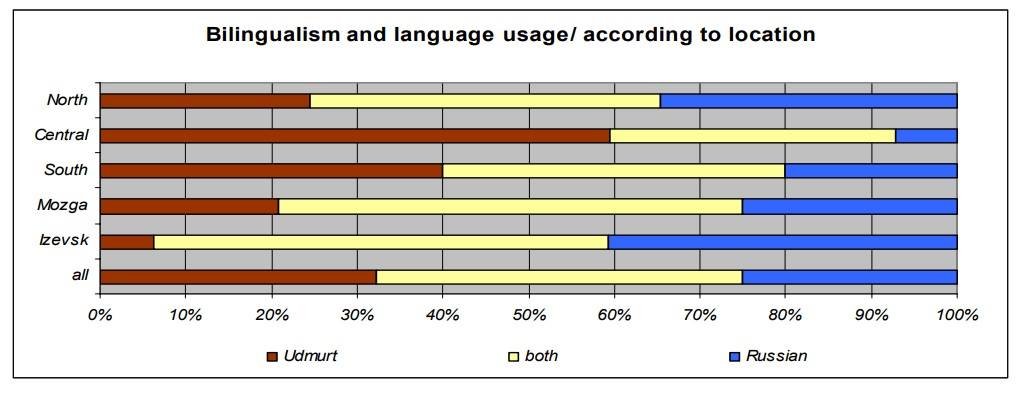

The place of residence and the demographic situation clearly determine whether a speaker has any chance to practice his mother-tongue. Accordingly, Udmurt is used generally in the largest proportion among the respondents of the Southern and Central regions, and in the smallest proportion among the urban Udmurts. The use of Russian is the most typical of respondents in Izsevszk and speakers in the Northern region, but it is not exclusive as approximately 50% of them use both languages alike.

It is, however, difficult to make generalisations about certain locations, as each of them can be considered unique. Sometimes the speakers of the Southern region, other times the speakers of the Northern region have more opportunities to speak Udmurt, as the choice of language in the different locations of language usage is unique in every area of residence, in every village.

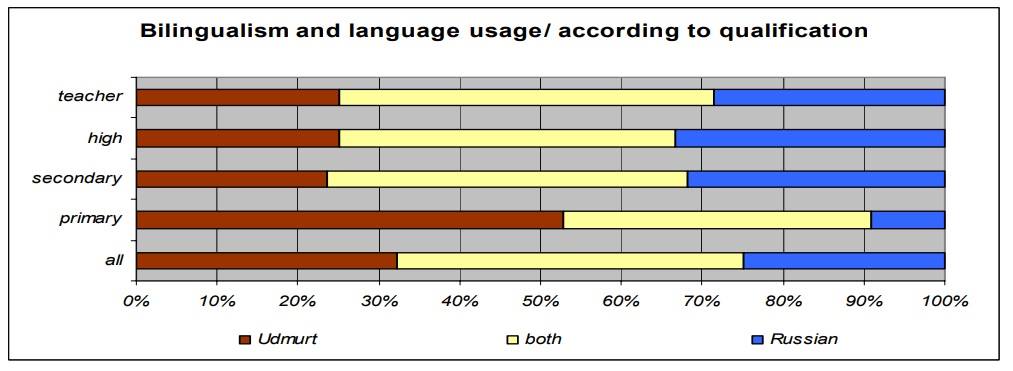

Having higher education qualification is not favourable to the Udmurt language usage: only people with primary qualification use Udmurt alone or mainly in the communication with different discussion partners and in the various locations. Accordingly, the written usage of the language, which is frequent among the younger and more educated respondents, is characterised by the dominance of the Russian language.

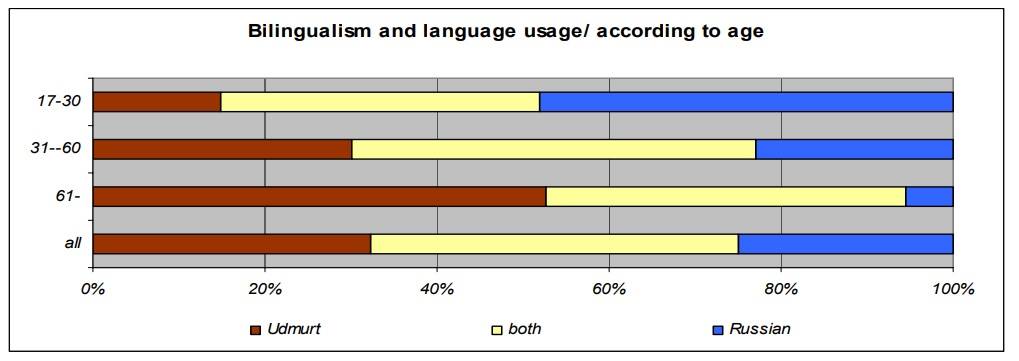

On the whole, it can be stated that nearly half of the respondents use both Russian and Udmurt alike. The exclusive or predominant use of the Udmurt language is mostly typical of the language usage of the elderly. By comparison, the usage of the Udmurt language among the middle-aged and the youth shows a sharp decline. The exclusively Udmurt communication among the middle-aged has reached a minimum level. The proportion of people using both languages is slightly higher in the group of the middle-aged than among the elderly, but around the same – almost half of the groups – as in the age group of the under 30.

The use of the Russian language shows different proportions in the age groups: parallel to the decrease of age the use of Russian increases following the decline in the use of the Udmurt language. So Udmurt is not succeeded by the usage of both languages but the predominant or exclusive use of Russian. In the age group of the under 30 there are people who speak only Russian.

Accordingly, the easier language is Udmurt for the older generations and Russian for the younger ones.

From the viewpoint of the future survival of the language that would be promising if the number of people using both languages did not fall, if the bilingualism of this considerable size group showed a relative stability.

However, the data indicates that the decrease of age is followed by a decline in the proportion of people speaking both languages and by an increase in the proportion of those who use exclusively or predominantly Russian.

The proportion of those who speak only the standard form of Udmurt is insignificant, the overwhelming majority speak only in dialect or in dialect as well. However, the age differences are characteristic: the use of dialect is less and less present among the younger speakers.

The recipients favour Udmurt when discussing family matters, personal feelings and life, while they consider it proper to use Russian when speaking about social issues. It deserves, however, attention that among the youth the proportion of those who prefer speaking in Udmurt has already halved. They are the ones who do not experience language change, probably in connection with their less frequent language use. In their opinion there is no subject that can be discussed better in Udmurt. The young people are also those – in addition to the speakers in the Southern region – who see the future of the Udmurt language in the most pessimistic way.

The education of Udmurt is considered important independently from the age of the respondents, around fifty percentage of them share the opinion that everybody should learn Udmurt in the Udmurt Republic.

The spoken language characterised by frequent changes of code due to the everyday use of both languages is looked on as inappropriate. It is possible, that this attitude also contributes to the fact that on certain domains of language usage Udmurt is forced into the background.

It is not typical any more that somebody is rebuked for speaking Udmurt in a public area. One possible explanation is a positive change in the social public thinking, the other is the less frequent use of the Udmurt language.

In the basis of the above characterised language usage and relation with the language I compiled a general index of language usage, which illustrates the summary of the individual examined groups’ language usage. The index was defined on the basis of the weighted evaluation of selected issues concerning language usage and relation with a language. The following graph illustrates this.

Concerning the speakers’ choice of grammatical variables the following can be stated.

The judgement on certain dialectal phenomena is influenced by the dialectal background, but not to a decisive degree. In the judgments on several grammatical variables with dialectal background there are no irreconcilable differences among those respondents who live in various dialectal areas. The use of the dialectal variants shows a decreasing tendency mainly among the young.

The opinion about those linguistic phenomena that can be explained by the Russian contact effect – morphological, syntactic and lexicological variables – is not uniform. The speakers generally consider the characteristically Russian structures also good, the young to a larger extent than the elderly people.

Between an Udmurt word of the language revival and its equivalent Russian loan word the speakers tend to choose the common Russian loan word, while they usually regard the Udmurt word also appropriate.

In the case of certain variants of some variables- loan verbs, morphological variables with dialectal background – the spontaneous linguistic form strongly deviates from the literary norm taught at school and used in the media. It might not be too bold to assume that the use of the Udmurt language in as many domains of language usage and with as many discussion partners as possible could be helped, if the use of non-standard linguistic variables – either with dialectal background or Russian borrowings – were not connected with institutionally negative value judgement.

As a final conclusion it can be stated that since the rival of the Udmurt language in respect of usage is the Russian language that has high reputation and long literary history and consequently a set standard, only an Udmurt language used in a wide circle of functions and with a set standard can be a match for it.

The acquisition and use of this language, however, cannot be imagined without its widespread usage at schools. It is extremely important that the speakers do not change to monolingual Russian communication, but use and be able to use both languages in as many domains as possible. Accordingly, paying attention to the language usage of those speakers who use both languages is worth and necessary.

Zsuzsanna Salánki, Eötvös Loránd University Faculty of Arts. Budapest, 2007.

Leave a Reply