Chuvash in the empire of ХІХ century

We have collected and structured what various travelers and ethnographers from Muscovy wrote about the Chuvash and what kind of future they wished for the Chuvash.

Attitude towards neighbors

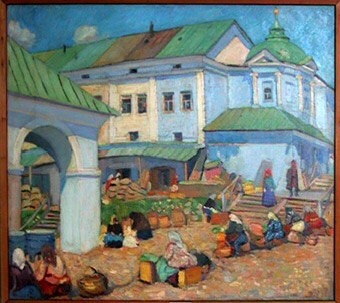

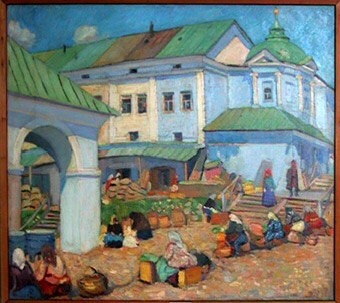

Their bazaars are located on the road in the field, like many other Chuvash bazaars, or small agricultural fairs. The Chuvash do not like the influx of strangers into their villages and shun any contacts with other peoples. Frequent relations with the Russians, increased commercial and industrial activities also changed the concept of the Chuvash in many respects. The monopoly of Russians in the Chuvash bazaars has disappeared: for the most part, the Chuvash both procure or buy things necessary for household use in Kazan and county towns, and sell them at their bazaars.

Everyday life

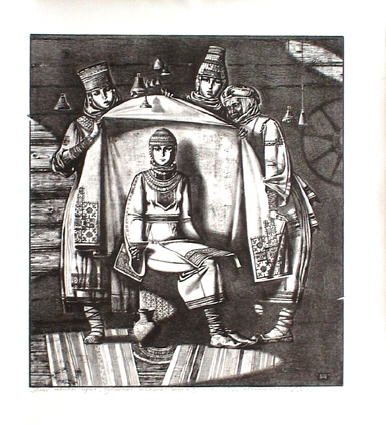

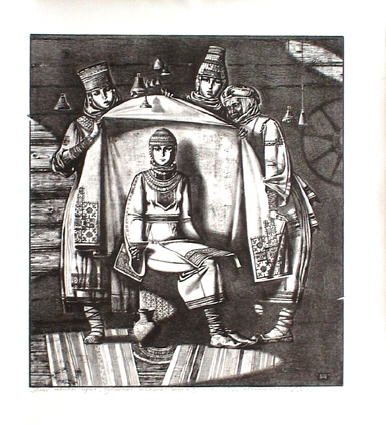

When the there is a wedding, the Chuvash reward their daughters better than Russian peasants. Chuvash gives his daughter from everything he has; he gives her a cow, several sheep, all the domestic birds in pairs, and a wagon with a horse and all the harness. Daughters are married off quite late.

The Chuvash commemorate four times a year: in spring, summer, autumn and winter. Three times, as I saw and explained in my letters, and the fourth time in the spring in Semik. On this day, they commemorate the dead at the graves, and these commemorations happen to be more ceremonial than others.

Usually the Chuvash bring wine, beer and various foods with them to the cemetery. Half of all supplies are laid and poured on the graves, and the other half they drink and have fun with dancing; they even leave a lot of clothes, shirts, caftans and women’s clothes on the graves. The Russians also gather for these commemorations not less than the Chuvash; the first usually, take with them everything donated by the Chuvash to the dead at the end of the holiday.

Bread and provisions are fed to poultry, and clothes are worn by themselves; however, only poor Russian peasants do this.

During my trip to Nizhnii-Novgorod, where, by the Highest command, I was sent in 1831 to take measures to stop the epidemic of cholera, I found some remarks about Cheboksary district and the Chuvash – cholera did not penetrate to the Chuvash, the reason of which was probably their smoky houses.

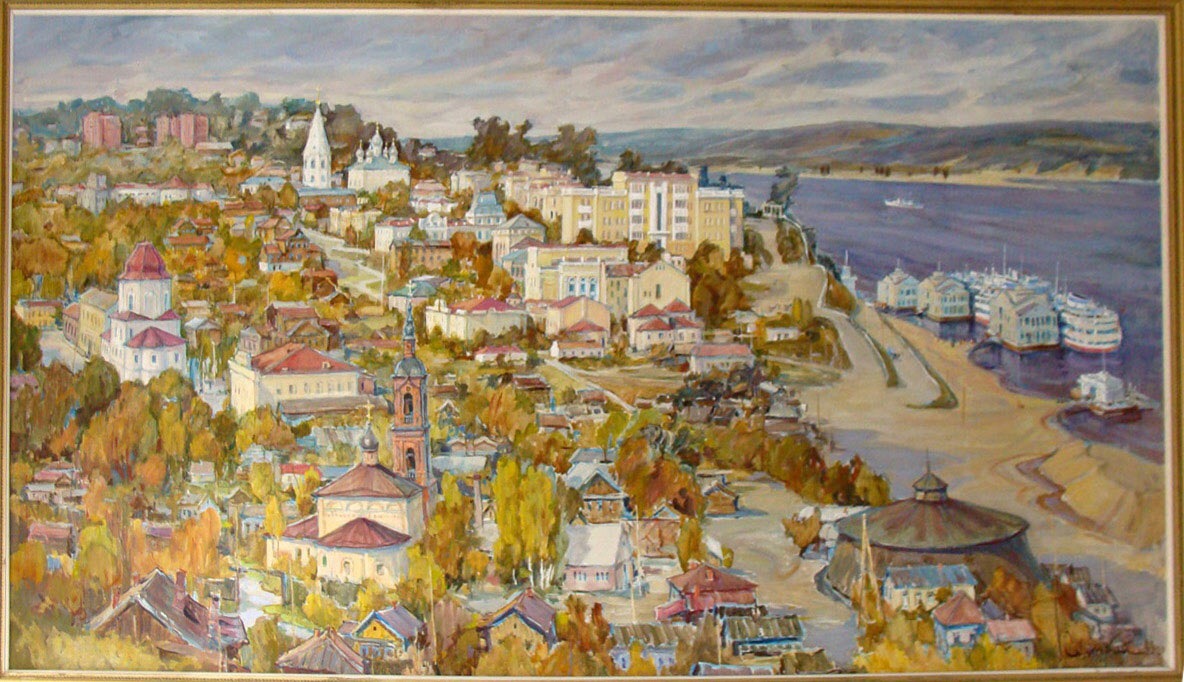

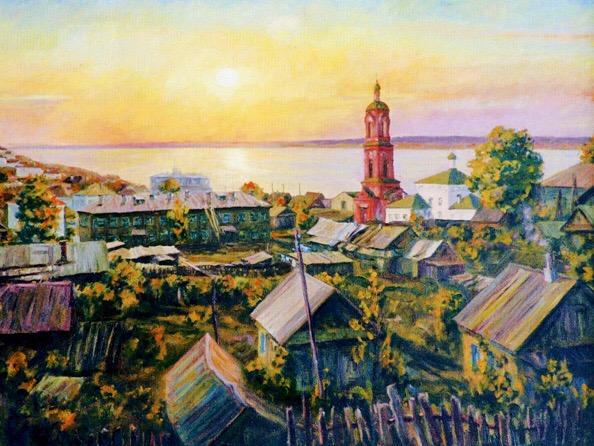

By the way, I will cite a small remark from Anorov’s work: the Chuvashs live incomparably better than many Russian peasants. Their villages are a collection in one place of several hamlets, or estates. There are no correct streets; on the other hand, you can hardly find such cleanliness in the yard and such healthy air at a Russian peasant as in a Chuvash. Their construction is not beautiful for the eyes, but beauty and perspective are needed in the cities, and the villager needs convenience in everything; the Chuvash has everything at hand: a house with a threshing floor and all the hangars; arable land is nearby, and not like the Russians have, sometimes 15 versts away; the forest is close, there is plenty of bread left and with a significant sale on the piers for both capitals; there are almost no beggars among them.

National language

I wanted to translate the names of their months in Russian; but the Chuvash, not knowing the Russian language well, do not know how to do it; you need to ask a Russian priest who knows the Chuvash language well.

The Chuvash assured me that they had little understanding of the gospel read by a Russian priest in their language, it is the proof that either we cannot pronounce their sounds correctly, or the translation is insufficient.

The Chuvash will never learn to pronounce our words perfectly and correctly. No matter how you force him, you will never make him pronounce correctly, for example, the Russian d, especially at the beginning of a word; he will always pronounce t. I know the grandson of a Russified Chuvash; he does not understand a word from the language of his grandfather, but he still pronounces the fatal d as t.

The Chuvash language consists of the words of the proper Chuvash, Tatar and a very small number of Russian. The Chuvash, having no writing, keep their language according to the tradition. It is due to moving away from education their language is not enriched with the time, or is not completely lost.

Consequences of life in the empire

Christianization

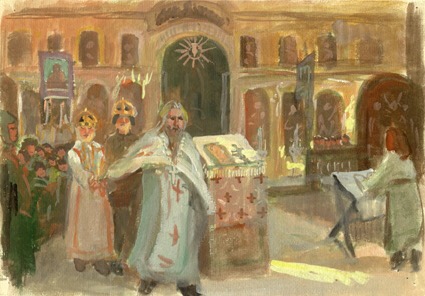

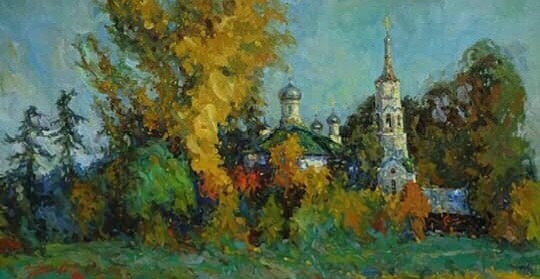

Entering the borders of the Chuvash land, I was pleasantly surprised by the change that I had least hoped to see there. Imagine: in Petrovki, i.e. at a time when the semi-pagan Chuvash land was celebrating one of its most important holidays and making the most abundant sacrifices to the gods – at that time I saw a divine service with bows in a Christian church.

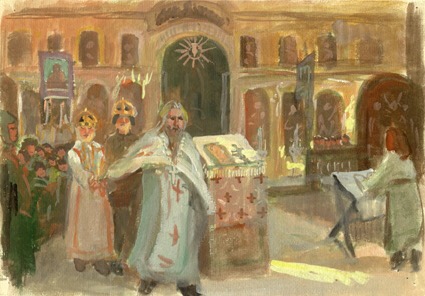

Converted to Christianity (about 106 years ago), not by persuasion, but by force, they had not the slightest idea of the truths of our religion. They were baptized themselves, baptized their children, in case of illness they went to confession and communed the Holy Mysteries, not at all understanding what they were doing.

They saw in the priests informers, enemies, their persecutors; and they interpreted their most legitimate actions in their own way, and they attributed them a different meaning. It should, however, be said that, in general, the Russians, from the very conquest of this place, probably treated the Chuvash very harshly. Thus, the latter tried, as much as possible, to move away from the attention of the winners. They settled as far as possible from the main roads, navigable rivers, at some dirty stream, and along the slopes of two hollows. Almost every Chuvash village is located in such a way that you will notice it only when you stick your nose into it. It was considered a duty, a matter of honor for everyone to hide from the Russians the road to the villages villages of the Chuvash.

But after many stops, detours, crossings and entries, you finally got to the village through which your path lies.

As soon as you have moved beyond the outskirts, the children who were playing in the streets rush headlong to their homes with a cry: vyras! vyras! (Russian! Russian!).

In an instant all the gates are locked, all the doors are shut, nowhere the human soul is visible; the whole village seemed to have died out from a pestilence.

Russification

The Chuvash, who live on the main roads, have already become smarter, or, as they say, Russified.

Koshtan is the name of the Chuvash who is the most active in the village and knows the Russian language well. They always send a koshtan to solve village affairs and agree with him in everything.

They have no idea about birkas, that is, Chuvash characters, and tamgas; and who knows how to write and read in Russian, he is called tiek, i.e. scribe.

Versta, in Chuvash “sehrom”. They do not measure the road in their own way, but consider it to be our versts and know that before a verst contained 700 sazhen, and now five hundred. Telyuksel chalash 700, sitsesel-chalash 500 sazhen.

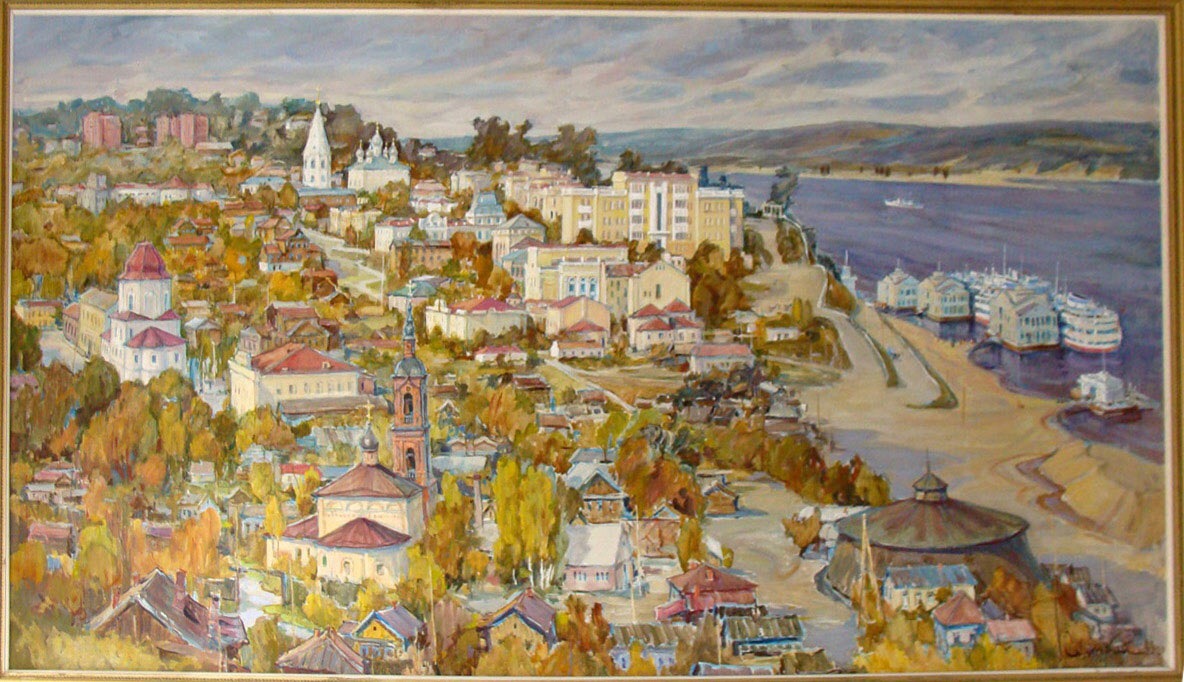

One of them is revered as the most educated who traveled along high roads, drove a Russian to the Nizhnii Novgorod fair, visited a county or provincial city, or pulled a vessel from Cheboksary to Rybinsk.

Chuvash children, like Russian boys, are reluctant to take up a book, but on the other hand, they get used to it almost faster than Russians. A year later, they learn to read fluently and speak Russian fluently.

Indeed, now very few of the Chuvash do not know our language at all. Many speak it so freely that only an accustomed to their dialect and understanding ear can recognize them as Chuvash. Even hir-arym, the female gender, who is still aloof from the Russians and has very little contact with them, is not completely alien to some knowledge of our language. (Justice requires, however, to note that the Chuvash women only pronounce harder Russian words, but combine them in their own way, because our word composition is really hard to them. That is why it is sometimes very difficult to understand them.

This shortcoming occurs, in my opinion, because they began to study Russian already in adulthood.)

Chuvash calles a dos a person to whom he made a vow of inseparable friendship. It is necessary to think that initially those who became dos, giving a vow of friendship, gave each other the best each had, and thus symbolically expressed their readiness to sacrifice everything for the dos.

Thus, mutual gifts constituted a ritual at the conclusion of friendship.

Under the influence of the Russians, who knew how to extract their benefits from both the bad and good traits of the Chuvash, this rite lost its original meaning.

A Russian buys a trifle, for example, a plush hat, a silk sash, or a two-ruble coat, and hurries with this gift to a rich Chuvash; and that, in the simple conviction that this is the best thing his friend has, gives him one or two best hives of bees, a horse, a cow, or some other valuable property.

Finally, the Chuvashs saw that their Russian friends were not dos at all, that they were hiding selfish thoughts under the sacred name of friendship, and began to repay them al pari, or not to do dos with them at all. Thus dos now exist only in name; and I am convinced that the famous phrase: “My friends! there are no more friends in the world,” was originally pronounced in the Chuvash language by some disappointed “Vasiliy Ivanovich”, and it was pronounced as follows: “my dos! neither in Tsivilskiy, nor in Yadrinskiy, nor in Buinskiy, nor in Kurmysh, nor even in Cheboksary district – there are no more dos! The Russians exterminated, destroyed, wiped acquaintances off the face of the earth not with sivukha, not with March beer, not with honey, but with tea, white wine, French and Kizlyar vodka.”

Why did the Russians decide to call the Chuvash Vasiliy Ivanovich? Perhaps this nickname comes from the fact that the priests originally gave the newborn Chuvashchildren the most commonly used and most famous names. And what name is more common than Vasiliy and Ivan?

The last limit to which their ambition strives is kinship with the Russians – the Chuvash have a custom to marry their daughters off for sure to foreign villages.

Marry a daughter off to a Russian, or marrying a son to a Russian is the height of well-being for an aristocratic Chuvash.

Thus, time itself is preparing to finally resolve the question, which in the days of the existence of the Bible Society, was the subject of a strong dispute: is it possible to completely Russify the Chuvash, Cheremis and other small peoples living in Russia and already professing Christian faith? At the present time, it is already possible to answer this question in no other way than in the affirmative; it can i.e. be assumed that someday they will completely forget both their language and their way of life, especially since the elements of this life are meager and have not the slightest connection either with their real religion or with their historical memories.

Literature:

1. A. Fuks, K. Fuks. Notes on the Chuvash and Cheremis of Kazan Province. Kazan, 1840.

2. Chuvash antiquity

Vasiliy Sboev. Studies on foreigners in Kazan province. Notes on the Chuvash (Letters to the editor of Kazan Provincial Vedomosti), 1851.

3. Statistical note on the peoples inhabiting Saratov province.

See Moscow Telegraph, 1833, No. 13. (Stat. description of Saratov province by L. Leopoldov. 1839, p. 41.).

4. (Zavolzhskiy ant, 1832, No. 20.).

5. Chuvash, their origin and beliefs. O. I. Senkovskiy. vol. VI-1895.

On the backdrop of an increasingly active absorption by the empire of the still existing Chuvash people, when the Chuvash declare that their native language is Russian, and also claim that they have nothing to share with the Russians and that they are ready to die for Kremlin empire, it is necessary to remember how, who and when began to form the current subordinate and mankurtized position of the Chuvash people.

We have collected and structured what various travelers and ethnographers from Muscovy wrote about the Chuvash and what kind of future they wished for the Chuvash.

Attitude towards neighbors

Their bazaars are located on the road in the field, like many other Chuvash bazaars, or small agricultural fairs. The Chuvash do not like the influx of strangers into their villages and shun any contacts with other peoples. Frequent relations with the Russians, increased commercial and industrial activities also changed the concept of the Chuvash in many respects. The monopoly of Russians in the Chuvash bazaars has disappeared: for the most part, the Chuvash both procure or buy things necessary for household use in Kazan and county towns, and sell them at their bazaars.

Everyday life

When the there is a wedding, the Chuvash reward their daughters better than Russian peasants. Chuvash gives his daughter from everything he has; he gives her a cow, several sheep, all the domestic birds in pairs, and a wagon with a horse and all the harness. Daughters are married off quite late.

The Chuvash commemorate four times a year: in spring, summer, autumn and winter. Three times, as I saw and explained in my letters, and the fourth time in the spring in Semik. On this day, they commemorate the dead at the graves, and these commemorations happen to be more ceremonial than others.

Usually the Chuvash bring wine, beer and various foods with them to the cemetery. Half of all supplies are laid and poured on the graves, and the other half they drink and have fun with dancing; they even leave a lot of clothes, shirts, caftans and women’s clothes on the graves. The Russians also gather for these commemorations not less than the Chuvash; the first usually, take with them everything donated by the Chuvash to the dead at the end of the holiday.

Bread and provisions are fed to poultry, and clothes are worn by themselves; however, only poor Russian peasants do this.

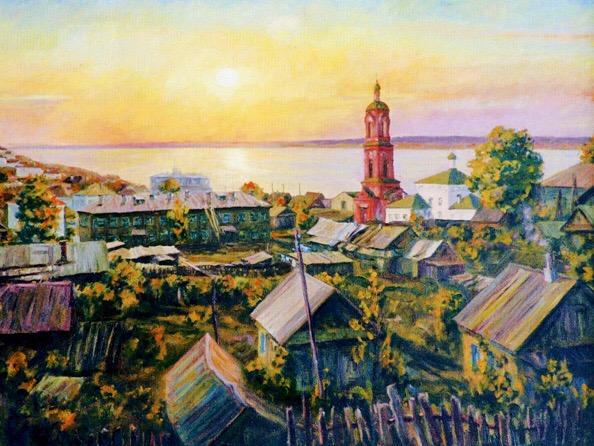

During my trip to Nizhnii-Novgorod, where, by the Highest command, I was sent in 1831 to take measures to stop the epidemic of cholera, I found some remarks about Cheboksary district and the Chuvash – cholera did not penetrate to the Chuvash, the reason of which was probably their smoky houses.

By the way, I will cite a small remark from Anorov’s work: the Chuvashs live incomparably better than many Russian peasants. Their villages are a collection in one place of several hamlets, or estates. There are no correct streets; on the other hand, you can hardly find such cleanliness in the yard and such healthy air at a Russian peasant as in a Chuvash. Their construction is not beautiful for the eyes, but beauty and perspective are needed in the cities, and the villager needs convenience in everything; the Chuvash has everything at hand: a house with a threshing floor and all the hangars; arable land is nearby, and not like the Russians have, sometimes 15 versts away; the forest is close, there is plenty of bread left and with a significant sale on the piers for both capitals; there are almost no beggars among them.

National language

I wanted to translate the names of their months in Russian; but the Chuvash, not knowing the Russian language well, do not know how to do it; you need to ask a Russian priest who knows the Chuvash language well.

The Chuvash assured me that they had little understanding of the gospel read by a Russian priest in their language, it is the proof that either we cannot pronounce their sounds correctly, or the translation is insufficient.

The Chuvash will never learn to pronounce our words perfectly and correctly. No matter how you force him, you will never make him pronounce correctly, for example, the Russian d, especially at the beginning of a word; he will always pronounce t. I know the grandson of a Russified Chuvash; he does not understand a word from the language of his grandfather, but he still pronounces the fatal d as t.

The Chuvash language consists of the words of the proper Chuvash, Tatar and a very small number of Russian. The Chuvash, having no writing, keep their language according to the tradition. It is due to moving away from education their language is not enriched with the time, or is not completely lost.

Consequences of life in the empire

Christianization

Entering the borders of the Chuvash land, I was pleasantly surprised by the change that I had least hoped to see there. Imagine: in Petrovki, i.e. at a time when the semi-pagan Chuvash land was celebrating one of its most important holidays and making the most abundant sacrifices to the gods – at that time I saw a divine service with bows in a Christian church.

Converted to Christianity (about 106 years ago), not by persuasion, but by force, they had not the slightest idea of the truths of our religion. They were baptized themselves, baptized their children, in case of illness they went to confession and communed the Holy Mysteries, not at all understanding what they were doing.

They saw in the priests informers, enemies, their persecutors; and they interpreted their most legitimate actions in their own way, and they attributed them a different meaning. It should, however, be said that, in general, the Russians, from the very conquest of this place, probably treated the Chuvash very harshly. Thus, the latter tried, as much as possible, to move away from the attention of the winners. They settled as far as possible from the main roads, navigable rivers, at some dirty stream, and along the slopes of two hollows. Almost every Chuvash village is located in such a way that you will notice it only when you stick your nose into it. It was considered a duty, a matter of honor for everyone to hide from the Russians the road to the villages villages of the Chuvash.

But after many stops, detours, crossings and entries, you finally got to the village through which your path lies.

As soon as you have moved beyond the outskirts, the children who were playing in the streets rush headlong to their homes with a cry: vyras! vyras! (Russian! Russian!).

In an instant all the gates are locked, all the doors are shut, nowhere the human soul is visible; the whole village seemed to have died out from a pestilence.

Russification

The Chuvash, who live on the main roads, have already become smarter, or, as they say, Russified.

Koshtan is the name of the Chuvash who is the most active in the village and knows the Russian language well. They always send a koshtan to solve village affairs and agree with him in everything.

They have no idea about birkas, that is, Chuvash characters, and tamgas; and who knows how to write and read in Russian, he is called tiek, i.e. scribe.

Versta, in Chuvash “sehrom”. They do not measure the road in their own way, but consider it to be our versts and know that before a verst contained 700 sazhen, and now five hundred. Telyuksel chalash 700, sitsesel-chalash 500 sazhen.

One of them is revered as the most educated who traveled along high roads, drove a Russian to the Nizhnii Novgorod fair, visited a county or provincial city, or pulled a vessel from Cheboksary to Rybinsk.

Chuvash children, like Russian boys, are reluctant to take up a book, but on the other hand, they get used to it almost faster than Russians. A year later, they learn to read fluently and speak Russian fluently.

Indeed, now very few of the Chuvash do not know our language at all. Many speak it so freely that only an accustomed to their dialect and understanding ear can recognize them as Chuvash. Even hir-arym, the female gender, who is still aloof from the Russians and has very little contact with them, is not completely alien to some knowledge of our language. (Justice requires, however, to note that the Chuvash women only pronounce harder Russian words, but combine them in their own way, because our word composition is really hard to them. That is why it is sometimes very difficult to understand them.

This shortcoming occurs, in my opinion, because they began to study Russian already in adulthood.)

Chuvash calles a dos a person to whom he made a vow of inseparable friendship. It is necessary to think that initially those who became dos, giving a vow of friendship, gave each other the best each had, and thus symbolically expressed their readiness to sacrifice everything for the dos.

Thus, mutual gifts constituted a ritual at the conclusion of friendship.

Under the influence of the Russians, who knew how to extract their benefits from both the bad and good traits of the Chuvash, this rite lost its original meaning.

A Russian buys a trifle, for example, a plush hat, a silk sash, or a two-ruble coat, and hurries with this gift to a rich Chuvash; and that, in the simple conviction that this is the best thing his friend has, gives him one or two best hives of bees, a horse, a cow, or some other valuable property.

Finally, the Chuvashs saw that their Russian friends were not dos at all, that they were hiding selfish thoughts under the sacred name of friendship, and began to repay them al pari, or not to do dos with them at all. Thus dos now exist only in name; and I am convinced that the famous phrase: “My friends! there are no more friends in the world,” was originally pronounced in the Chuvash language by some disappointed “Vasiliy Ivanovich”, and it was pronounced as follows: “my dos! neither in Tsivilskiy, nor in Yadrinskiy, nor in Buinskiy, nor in Kurmysh, nor even in Cheboksary district – there are no more dos! The Russians exterminated, destroyed, wiped acquaintances off the face of the earth not with sivukha, not with March beer, not with honey, but with tea, white wine, French and Kizlyar vodka.”

Why did the Russians decide to call the Chuvash Vasiliy Ivanovich? Perhaps this nickname comes from the fact that the priests originally gave the newborn Chuvashchildren the most commonly used and most famous names. And what name is more common than Vasiliy and Ivan?

The last limit to which their ambition strives is kinship with the Russians – the Chuvash have a custom to marry their daughters off for sure to foreign villages.

Marry a daughter off to a Russian, or marrying a son to a Russian is the height of well-being for an aristocratic Chuvash.

Thus, time itself is preparing to finally resolve the question, which in the days of the existence of the Bible Society, was the subject of a strong dispute: is it possible to completely Russify the Chuvash, Cheremis and other small peoples living in Russia and already professing Christian faith? At the present time, it is already possible to answer this question in no other way than in the affirmative; it can i.e. be assumed that someday they will completely forget both their language and their way of life, especially since the elements of this life are meager and have not the slightest connection either with their real religion or with their historical memories.

Literature:

1. A. Fuks, K. Fuks. Notes on the Chuvash and Cheremis of Kazan Province. Kazan, 1840.

2. Chuvash antiquity

Vasiliy Sboev. Studies on foreigners in Kazan province. Notes on the Chuvash (Letters to the editor of Kazan Provincial Vedomosti), 1851.

3. Statistical note on the peoples inhabiting Saratov province.

See Moscow Telegraph, 1833, No. 13. (Stat. description of Saratov province by L. Leopoldov. 1839, p. 41.).

4. (Zavolzhskiy ant, 1832, No. 20.).

5. Chuvash, their origin and beliefs. O. I. Senkovskiy. vol. VI-1895.

Leave a Reply